Address

Room 2301C, 23rd Floor, Building 1, jinghu Commercial center, No, 34, Liangzhuang Street, Eri District, Zhengzhou City, Henan province

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Address

Room 2301C, 23rd Floor, Building 1, jinghu Commercial center, No, 34, Liangzhuang Street, Eri District, Zhengzhou City, Henan province

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Introduction to TPE

Thermoplastic elastomers (TPEs or TPRs) are thermoreversibly crosslinked materials that can be processed as thermoplastics (i.e., melt-processed). They exhibit elastic behavior similar to traditional vulcanized or chemically crosslinked elastomers: they possess the elasticity of rubber at room temperature and are plasticizable at high temperatures.

Since the discovery of polyurethane TPEs by Bayer in Germany in 1938, the development of styrene-butadiene-styrene block polymer TPEs by Phillips and Shell in the United States in 1963 and 1965, and the start of mass production of olefin-based TPEs in the United States, Europe, and Japan in the 1970s, continuous technological innovation has led to the emergence of new TPE varieties, forming the vast TPE market today and significantly advancing the integration of the rubber and plastics industries. The TPEs that have been industrially produced in the world include: styrenes (SBS, SIS, SEBS, SEPS), olefins (TPO, TPV), dienes (TPB, TPI), vinyl chlorides (TPVC, TCPE), urethanes (TPU), esters (TPEE), amides (TPAE), organic fluorines (TPF), silicones and ethylenes, etc., covering almost all areas of current synthetic rubber and synthetic resins.

Phase structure of TPE

The structure of most thermoplastic elastomers is characterized by a hard phase and a soft phase with distinct chemical bond compositions, forming a phase-separated system. One phase is hard and solid at room temperature, called the hard phase (or resin phase); the other is an elastomer, called the soft phase (or rubber phase). Typically, the two phases are chemically bonded through block or grafting.

The hard phase imparts strength to the thermoplastic elastomer and acts as a physical crosslink. The soft phase provides flexibility and elasticity to the system. When the hard phase is melted or dissolved in a solvent, the material can flow and can be processed using common processing methods. Upon cooling or solvent evaporation, the hard phase hardens, and the material regains its strength and elasticity, demonstrating the plastic processing characteristics of thermoplastic elastomers.

The polymers that comprise the respective phases retain most of their properties, resulting in each phase exhibiting a specific glass transition temperature (Tg) or crystalline melting temperature (Tm). Tg and Tm can be used to determine the transition points in the physical properties of a particular elastomer.

How TPE is manufactured

Thermoplastic elastomers are generally classified into two main categories based on their preparation methods: chemically synthesized thermoplastic elastomers and rubber-plastic blends. The former appear as standalone polymers and can be categorized as backbone copolymers, graft copolymers, or ionic copolymers. The latter primarily consist of blends of rubber and resin, including crosslinked vulcanized dynamic vulcanizates (TPE-TPV) and interpenetrating polymer networks (TPE-IPN).

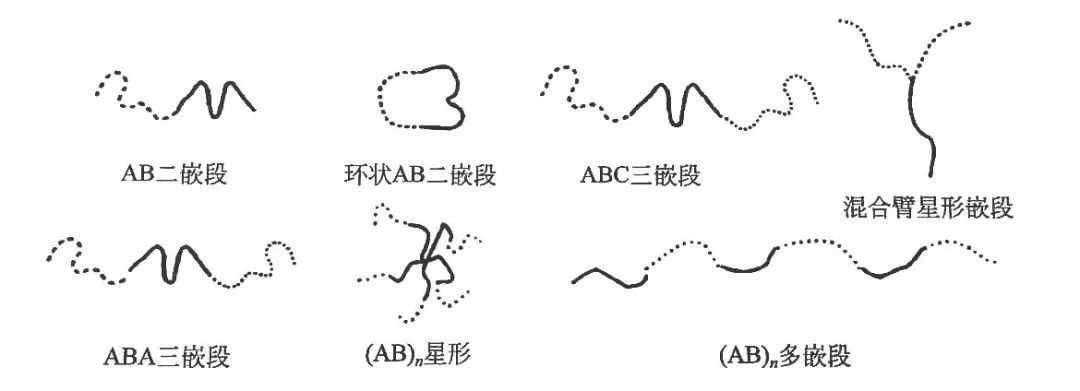

Most industrially produced thermoplastic elastomers belong to the first category: chemically synthesized block copolymers, composed of two or more polymer chains linked at their ends. Linear block copolymers consist of two or more polymer chains linked sequentially, while star block copolymers consist of two or more linear blocks linked to a common branch point. The block copolymer structure is shown in the figure.

Most block copolymers are prepared by several controlled polymerization methods.

Anionic polymerization is a well-established method for synthesizing specialized block copolymers. Polydispersity (Mw/Mn < 1.05) can be achieved through anionic polymerization. Industrially, anionic polymerization is used to prepare several important types of block copolymers, including S-B-S and S-I-S TPEs.

Three common monomers are suitable: styrene (including substituted styrenes), butadiene, and isoprene. The solvent typically used is an inert hydrocarbon such as cyclohexane or toluene. Oxygen, water, and any other impurities must be completely eliminated to prevent undesirable reactions with highly reactive propagating species. These measures ensure precise control of the copolymer’s molecular weight.

Carbocationic polymerization is used to polymerize monomers that cannot be polymerized anionically. For example, it is used in the synthesis of styrenic thermoplastic elastomers containing S-IB-S isobutylene monomers, such as poly(styrene-b-isobutylene-b-styrene) (S-IB-S).

Living carbocationic polymerization is the latest technology for synthesizing styrenic block copolymers. It differs from anionic synthesis in that the polymerization system (i.e., the cationic mechanism) is slightly more complex than anionic polymerization, and the central (elastomer) block consists solely of polyisobutylene.

Controlled/Living Radical Polymerization (CLRP)

The principle of CLRP is to establish a dynamic equilibrium between a small fraction of growing free radicals and a large fraction of dormant species. For example, in conventional free radical polymerization, although only a small fraction of free radicals are present to prevent premature termination of polymerization, free radical growth and termination occur.

Coordination polymerization is performed using Ziegler-Natta or metallocene catalysts to prepare block polyolefin-based thermoplastic elastomers with controlled structures, such as OBC block copolymers.

Addition polymerization, using diisocyanates, long-chain diols, and chain extenders, to synthesize multiblock thermoplastic polyurethanes.

Other methods used to synthesize thermoplastic elastomers:

Dynamic vulcanization, used for thermoplastic vulcanizates;

Esterification and polycondensation, used for polyamide elastomers;

Transesterification, used for copolyester elastomers;

Catalytic polymerization of olefins, used for thermoplastic polyolefins (RTPOs);

Direct copolymerization, such as that of ethylene and methacrylic acid, to produce certain ionomeric thermoplastic elastomers.

Classification of thermoplastic elastomers

Known thermoplastic elastomers can be divided into the following seven categories:

① Styrenic block copolymers;

② Crystalline multiblock copolymers;

③ Other block copolymers;

④ Hard polymer/elastomer combinations;

⑤ Hard polymer/elastomer graft copolymers;

⑥ Ionomers;

⑦ Polymers with core-shell morphology.

Most thermoplastic elastomers are block copolymers or graft copolymers, composed of segments with different chemical and physical structures, typically designated by capital letters such as A, B, and C. These segments have a specific molecular weight, and even when separated, they retain the characteristics of a polymer. The arrangement of these segments defines the type of block copolymer.

Diblock copolymers are represented by A-B, indicating that the chain segments of component A are connected to the chain segments of component B. Triblock copolymers can be represented by A-B-A or A-B-C. Other options include (A-B)n or (A-B)nX.

An A-B-A triblock consists of two end blocks A connected to a central block B, while an A-B-C triblock consists of three blocks, each derived from a different monomer.

(A-B)n is an alternating block copolymer A-B-A-B, while (A-B)nX is a branched block copolymer with n branches, where n = 2, 3, or 4, and X represents a multifunctional attachment point. Branched block copolymers with n = 3 or more are called star block copolymers or star-branched block copolymers.

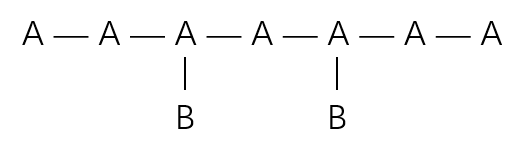

Using this terminology, graft copolymers can be represented as:

Advantages and disadvantages of thermoplastic elastomers

Thermoplastic elastomers offer various advantages over conventional vulcanized rubber materials:

① Fewer and simpler processing steps, as thermoplastic elastomers can be processed using the same methods as thermoplastics, significantly reducing costs and ultimately lowering the cost of the finished product.

② Shorter manufacturing times also reduce the cost of the finished product. Since thermoplastic elastomer molding cycles typically take seconds, compared to minutes for vulcanized rubber, equipment productivity is significantly improved.

③ Fewer or no ingredients are required. Most thermoplastic elastomers are supplied fully formulated and ready to manufacture.

④ Like thermoplastics, waste can be reused. However, waste utilization for vulcanized rubber is less efficient. In some cases, the amount of thermoset rubber waste can be as much as the weight of the molded part. Thermoplastic elastomer waste can be reground, and the resulting material has the same properties as the original material.

⑤ Faster molding cycles reduce energy consumption and make processing easier.

⑥ Simpler formulations and easier processing allow for better quality control and closer tolerances for finished parts.

⑦ Because thermoplastic elastomer resins offer greater repeatability and performance consistency, quality control costs are lower.

⑧ Because most thermoplastic elastomers have lower densities than conventional rubber compounds, their volumetric costs are generally lower.

Compared to conventional rubber materials, thermoplastic elastomers have the following disadvantages.

① They melt at high temperatures. This inherent property limits the use of thermoplastic elastomer parts to temperatures well below their melting point. Thermoset rubbers may be suitable for brief exposure to such temperatures. Recently, some thermoplastic elastomer materials have been developed for use at temperatures up to 150°C or higher.

② The number of low-hardness thermoplastic elastomers is limited. Many thermoplastic elastomers have a Shore A hardness of 80 or higher. Currently, the number of materials with a Shore A hardness below 50 has increased significantly, and some existing materials are gel-like.

③ Most thermoplastic elastomer materials require drying before processing. Conventional rubber materials almost never require drying, but drying is quite common during the manufacture of thermoplastics.